Paired kidney exchange draws Christiana Care patients to special meeting

Watch the NBC10 coverage of Ed and Mary Cole’s meeting with their paired donors, or click here to see more.

A deep sense of gratitude for the life-changing gifts they’d exchanged brought four people from around the country to a northern California restaurant on June 19.

Two had received kidneys and the other two had given them in a series of operations in early 2013. Among them were donor and recipient Ed and Mary Coyle, a Pike Creek couple whose transplants took place at Christiana Care.

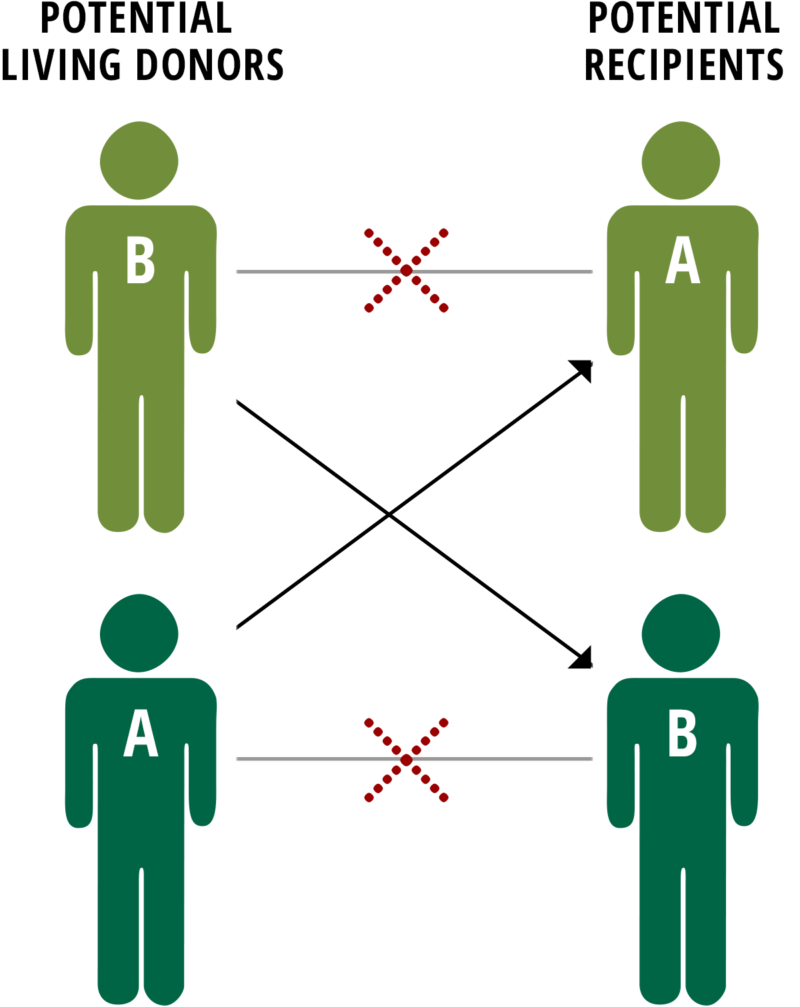

Because Ed couldn’t give Mary a kidney directly, he instead gave one to a stranger. In exchange, Mary received a compatible kidney from another person she didn’t know.

“I needed this man to understand how critical he was to saving my life,” Mary Coyle, a school librarian, said of Jason Klobchar, the San Diego man who donated a kidney to Mary.

Jody Campbell, the Modesto, California woman who received Ed’s kidney, brought her three children and four grandchildren to the June 19 meeting.

“I wanted Ed and Mary to see the gift that Ed had given me and how it had allowed me to see my daughters be married and my grandchildren be born,” said Campbell, whose relative donated a kidney, enabling her to join the paired donation exchange. “I probably wouldn’t have been here without that gift.”

It was, Mary Coyle said, a meeting of “chicken fingers and crying.”

The Christiana Care Kidney Transplant Program has participated in several of these paired kidney transplants since it began in 2007. Without these exchanges, Mary Coyle could have spent years waiting, in pain and frailty, for a kidney from a deceased donor.

“I remember not being able to get into church without taking a deep breath and being so tired,” she said.

Meetings like the one Mary helped organize in June are rare. Some donors are reluctant to form a relationship with the strangers who received their kidney. Many prefer to think of their donation as a gift to the loved one who received a kidney as a result. But this connection was driven by an abiding desire from both Mary Coyle and Jody Campbell to look their donors in the face and thank them.

A curated connection

Mary Coyle received her kidney at Christiana Hospital on Jan. 22, 2013. About 10 days would elapse before Campbell was ready for Ed’s kidney, so his operation had to wait. The fact that he went through with the donation, even after his wife received a kidney, speaks volumes about his character, Campbell said.

Though these four chose to meet, protecting the privacy of donors and recipients is of paramount importance to the Christiana Care team. As is typical in transplants at Christiana Care, Mary Coyle’s first contact with her donor was mediated by a social worker. Often, a recipient will mail a thank-you card, though it cannot include details that would identify the recipient or include contact information. Then, if a donor wants to have a conversation, a return card can be mailed through the hospitals.

“It’s like a stepping stone to regular communication,” said Emily Pruitt, MSN, RN, living donor coordinator at the Christiana Care Kidney Transplant Program.

After time has passed, the parties can communicate on their own. Campbell, who was curious from the start about her donor, reached out to Ed about a year after their surgery. Jason Klobchar, of San Diego, likewise sent Mary Coyle an e-mail about six months after their surgeries. Eventually, they decided to meet.

“All the kidneys were in the same room,” Mary Coyle said. “It was four of us in a room laughing, talking, taking pictures and marveling at our journey. I won’t say I didn’t cry, because I had been waiting for this for a long time.”

Klobchar, the San Diego man whose kidney was transplanted in Mary Coyle, said the transplant led him to eat better and exercise more.

“You’re more aware of your health,” he said. “You don’t have that second kidney, your insurance policy kidney,” he added, laughing.

He donated his kidney so that his sister, to whom he could not donate directly, could receive a kidney. Klobchar said his sister, who could not make the June rendezvous, does not know who donated her kidney because that person wishes to remain anonymous.

Linked by kidney

Because it is simpler and quicker, a direct kidney donation is a patient’s first choice. But incompatible blood types are not the only potential barriers to direct donation, Pruitt said.

Pregnancy, blood transfusions and previous transplants expose potential recipients to foreign factors called human leukocyte antigen (HLA) that are found on human cells. Recipients may respond by producing antibodies to HLA that are harmful to their new transplant if the antibodies match the HLA factors of the kidney donor. A test called a crossmatch is done to prove that each donor is safe for the recipient. Ms. Coyle had all three risks for antibody formation and developed many HLA antibodies that prevented her eldest son, her sister and her husband from directly donating to her based on this crossmatch.

Mary Coyle already knew about paired kidney donation, and immediately considered it as an option. Many other prospective recipients resign themselves to years of waiting if they are not a match for a loved one. That’s why Christiana Care’s Kidney Program discusses paired kidney donation from the very start, so that patients have it as an option if direct donation isn’t an option.

“What we’ve started to do is place education on paired kidney donation in the first packet patients receive and our first discussion after compatibility,” Pruitt said.

So, in late 2012, Mary Coyle’s medical information — her blood type, antibodies, and more — was placed in a database of potential donors and recipients. The computer compiled a list of potential donors, which was then screened by her Christiana Care medical team to find the best possible match.

Then, one day, a match offer arrived via email. And events moved quickly, as medical centers from across the country compiled information and reserved space in their operating rooms.

Managing match offers is multidisciplinary and multidepartmental work, Pruitt said, with a tight deadline attached. It’s all the more pressing because if even one match is rejected, the whole chain of transplants is at risk of falling apart.

If each transplant program accepts, they send blood samples to each other’s labs. A few days later, if the match holds, the kidneys are removed from their donors, flown across the country and are transplanted into their respective hosts.

The operations can happen simultaneously but, as in the Coyles’ case, don’t always. Delays between a couple’s transplants can work out for the best, Pruitt said, because one partner can recuperate, then care for the other.

After Mary Coyle’s operation, she awakened to the sight of one of her surgeons, Velma P. Scantlebury, M.D., FACS, associate chief of transplant surgery, waiting.

“That’s dedication, and you can’t get that anywhere else,” Mary Coyle said. “I don’t feel at all that I’m a patient there as much as part of the family.”

Finding a champion

Finding a kidney from a living donor should always be the first choice for a potential recipient. Since they’re taken from healthy adults, kidneys from living donors tend to last years longer than those from deceased donors. Even more daunting is the waiting — someone on a kidney donation list can expect to wait between six and eight years on average.

However, searching for someone to donate on your behalf requires difficult conversations.

The transplant program holds training sessions to help people find living donors, as well as what it calls a “Living Donor Champion.” This is a person who does not donate their kidney, but who can advocate on the patient’s behalf and spread the word.

“There’s somebody in your life who’s willing to do it,” said S. John Swanson III, M.D., FACS, chief of transplantation surgery at Christiana Care.

Getting yourself back

After months of using the elevator to get around her school, Downes Elementary in Newark, Coyle relished the chance to use the steps.

“Having that energy back and feeling like myself again was so awesome,” she said.

It was only after she returned that her colleagues told her how grey she’d looked before her surgery. Medically, she lives a normal life, which is all she really wanted, but still has one serious responsibility — being a steward of her gift.

“I work extremely hard to take care of it,” she said.