What if you had to:

- Choose between paying for a week of daycare or fixing the family car?

- Pawn a family valuable to pay a utility bill?

- Shop at a grocery store where no one spoke your language?

- Figure out where to live after being evicted from your apartment?

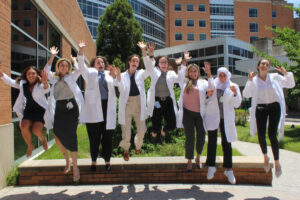

During an immersive simulation event organized by the Office of Health Equity, 95 new ChristianaCare residents were faced with these and other real-life scenarios that they were expected to navigate while also juggling work, family and medical needs.

Problems were the rule rather than the exception at the simulation, which meant residents – who were grouped together as “families” – had to contend with unsympathetic workers at social service agencies, exorbitant fees charged by payday lenders and job losses caused by excessive absences.

Sameer Akhtar, D.O., an internal medicine resident, took part in the simulation as a 10-year-old child on his own after saying goodbye to his parents who had to go to work. His older “sister” was kicked out of school and Akhtar was tasked with taking care of his little “brother.”

“It’s constant fear and doubt – when am I getting my next meal? When are my parents coming back? And I have to take care of a little one, but I’m only 10 years old. It really puts things into perspective,” Akhtar said.

‘This is not a game’

By struggling with the same kind of transportation issues, compounding money problems and family dynamics that their patients face, residents learn what it’s like to survive living week-to-week as a family living at or near poverty level.

“This is not a game,” said Jacqueline Ortiz, MPhil, vice president of Healthy Equity and Cultural Competency.

“At ChristianaCare, we want to make sure we are providing equitable access to good health care. The definition of health equity is that everybody gets an equal chance to be as healthy as they can be without it mattering how much money you make, who you are, where you live. Things like this poverty simulation help create a whole generation of physicians who are sensitized to that reality that not everybody comes from the same background.”

Four weeks in one hour

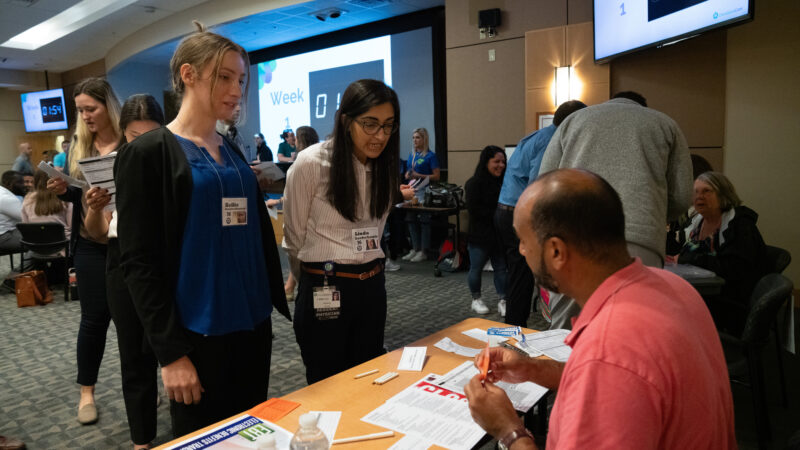

The interactive exercise simulated life challenges over the course of one month, with each week broken down in 15-minute increments. Residents were grouped into families of varying size, age and composition, each with distinct lived experiences.

Volunteers from ChristianaCare and other local organizations played assigned roles in the simulated community, including workers from the bank, child care, grocery store and social services. Their roles reflected the challenges people living in poverty face when trying to get help – bureaucracy, a lack of funding and institutional barriers to assistance.

“The struggle to pay rent, the struggle to have food, not knowing where you’re going to take your child, keeping your child home, being evicted – those are the real-life situations that our patients face,” said Erin Booker, LPC, chief Bio-Psycho-Social officer for ChristianaCare.

Suzanne Saunders Tait, a community educator with the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center & Research Institute, has participated in the simulation each time it has been conducted at ChristianaCare.

Tait, who portrayed a worker at the local community action agency, said it was important for residents to understand that there are processes to go through to get assistance. She listened empathetically to residents as they explained their challenges but inevitably responded the same way – “sorry, we can’t help you.”

It was a refrain heard repeatedly during the simulation. By the end, residents found themselves running across the John H. Ammon Medical Education Center as the stress from the experiences ramped up. In many cases, all it took was one unplanned event – such as getting sick – to cause a spiral of events to follow, including lost jobs for parents, problems in school for kids and no money for food or medicine.

From the residents:

- “It was very jarring to be in the situation and realize that no matter what you tried to do you still weren’t going to have enough money to survive. It was eye-opening to simulate living through that.”

- “My family had one bad week of bad luck, and it rolled so sharply into the following weeks that we ended up evicted at one point. It never really felt possible to dig ourselves out.”

“In most cases, you cannot walk into an agency and say the words, ‘I need’ and what you asked for just magically drops in your hands. If you do not qualify, then you do not get that need met,” Tait said.

“The reality is that the person may need to go to multiple organizations to get assistance.”

What poverty feels like

Manoj Philip, a personal finance coach who works with caregivers, was one of the most unpopular participants in the room. People dreaded having to talk to him, and some tried to avoid it as long as possible.

The reason why? Philip collected payments on loans in his role as banker.

As someone who has experienced poverty as an adult, Philip said he understood their reactions. He believes the simulation experience is a powerful way for residents to tap into their empathy, which can lead to compassion for their patients.

“I saw many residents handling their financial challenges in the same ways I handled mine in the past: with fear, shame, anxiety and distress,” he said.

Internal medicine resident Karlee Grudi, D.O., portrayed a 19-year-old with a 1-year-old child. She felt waves of frustration, guilt and disappointment as she left her child at home with a neighbor while she rushed around and tried to bargain with people to get what her family needed to survive.

Grudi said the time spent in the simulation was an important reminder that patients are facing other challenges other than what’s bringing them into a provider’s office.

“There’s just so much reliance on other people and it’s really hard to control everything that’s going on in your life,” Grudi said. “Imagine if you had any kind of disease, illness or sickness that happened to your family along with that. You’re like, ‘Wait, I have to wait three hours in the emergency room? I don’t have time for this.’ It just gave us a view into that life.”

Being the connection to services

Booker said with so much of a patients’ overall health impacted by the environment around them, it is critical for residents to understand the community they’re serving.

As part of a debriefing session following the simulation, Booker talked about working with different patient populations while Ortiz led a panel discussion about resources – including community health workers, health guides, Unite Delaware coordination network, Language Services and more – that are available at ChristianaCare.

Akhtar said the experience taught him to look more deeply at his patients rather than going through the checklist of symptoms that correspond with their diagnosis.

“Notice the small things, like their shirt is a little bit ruined or maybe they seem dehydrated. Ask them if they have food or if they had a ride here. You ask questions that matter so you can figure out if they’re going through something,” he said.

Laura Hernandez Vergara, who is part of the Community Health Outreach Team at the Graham Cancer Center, has already seen the benefits of the simulation.

“I have now run into some of the residents throughout the hospital and love to see them use an ChristianaCare interpreter for their Spanish-speaking patients,” said Hernandez, also a qualified medical interpreter.