Global health symposium highlights enormous challenges and opportunities

Thomas Quinn, M.D., certainly knew the statistics on AIDS deaths before he left for Uganda 15 years ago. He has authored more than 900 publications on HIV/AIDS.

The numbers really sank in, though, when Dr. Quinn landed in Kampala. As he left the airport, both sides of the road were lined with carpenters building thousands of wooden coffins.

“Global health really is a large public health issue, even if you’re not traveling around the globe.”

Five years later, the life-saving effect of antiretroviral drugs was instantly apparent. Dr. Quinn saw the same number of carpenters on the same road, but, this time, they were building furniture instead of coffins.

Dr. Quinn, associate director for international research at the National Institutes of Health and director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health, was keynote speaker at the Delaware Health Sciences Alliance Global Health Symposium at the John H. Ammon Medical Education Center, June 13. The event, which also featured global health leaders and educators from Christiana Care, focused on two very different locales where medical professionals can improve global health: less-developed countries overseas and closer to home in the U.S.

Dr. Quinn began researching global health in Africa in the 1970s, when it was still called “tropical medicine.” But the diseases he’s seeing now are much different from the ones he saw then. Communicable diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS are now overlapping with chronic diseases like obesity, cancer, diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in Africa. On top of that, there is a marked increase in mental illness driven by poverty, inequity, political upheaval, economic instability, severe weather events and unprecedented population growth.

He quoted “AJ” Daga Tola, a Nigerian musician and activist who lives in the overcrowded, fast-growing city of Lagos along with 21 million others: “Everyone here wakes up in anger. … People find it very hard, and it is getting worse.”

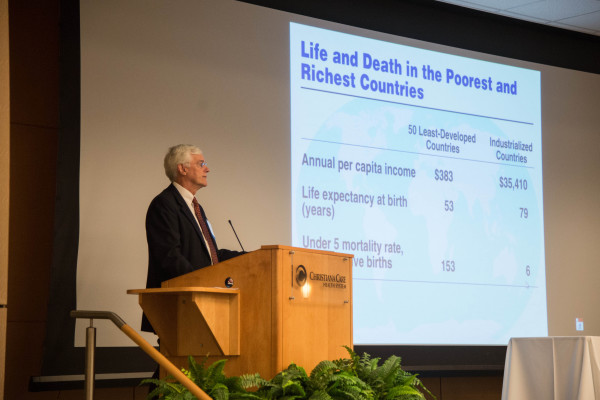

In the 50 least-developed countries, life expectancy at birth is 53, and annual per capita income is $383. In industrialized countries, life expectancy is 79 and per capita income is $35,410, Dr. Quinn said.

Health care accounts for 10 percent of the world GNP, and access to care is a growing issue.

Dr. Quinn flashed a quote from The Lancet on an overhead screen: “Health is now the most important foreign-policy issue of our time.”

The goal of global health is improving health for all people in all nations by promoting wellness and eliminating avoidable diseases, disabilities and deaths. Practitioners combine clinical care at the individual level and population-based measures to promote health.

Dr. Quinn sees the world response to the AIDS epidemic as one model for responding to other diseases. Deaths were averted as groups including the World Bank and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief funded efforts.

He explained how new technology helps treat patients and teach health-care providers continents away. Medical students in Uganda link to Johns Hopkins grand rounds via satellite. Telemedicine crosses continents. Doctors in remote areas receive mobile health information on their phones.

Still, he says, the number of physicians per 100,000 population varies widely: only two in Mozambique; 13 in Ghana; 164 in China; 280 in the U.S.; 340 in France; 417 in Russia; and 530 in Cuba.

He cited a litany of other health disparities. For example, 10 million of the 57 million worldwide deaths in 2010 were children younger than five. Ninety-eight percent of those children died in developing countries.

“There are opportunities to effect change in many of these areas,” Dr. Quinn said. “In terms of delivering health care and improving the lives of those affected, you can make huge differences. When I studied medicine as a student, I couldn’t get any funding. These opportunities weren’t there. They are now. Anyone who wants to go abroad — who wants to make a difference — those doors are now open.”

Interest in global health is growing at Christiana Care, where the first three residents with a global health track graduated in June and nine residents are currently enrolled. Of the 120 symposium attendees, more than half were students, residents and young physicians.

Christopher Prater, M.D., one of the first three graduates, said Christiana Care’s program is unique among global health tracks because it offers diverse instruction that includes surgery and gynecology, not just family medicine or pediatrics.

“Ours is a reflection of our culture at Christiana Care — collaborative and patient-centered and learner-centered without regard to silos,” said Omar A. Khan, M.D., MHS, director of the Global Health Residency Track in Family Medicine and chair of the DHSA Global Health Symposium.

Richard Derman, M.D., The Marie E. Pinizzotto, M.D., Endowed Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Christiana Care and a principal investigator of the Global Research Network for Women’s and Children’s Health, told attendees he found his life’s work while volunteering as a young Peace Corps physician in India.

“Just jump in, because, when you jump in, it’s not the same as hearing lectures,” he said. His jumping-in led to success in stemming the high number of maternal and infants deaths in India. His team’s interventions, including the use of oral misoprostol for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage, resulted in an approximate 50 percent reduction in postpartum hemorrhage among all study participants, the leading cause of maternal mortality both in India and worldwide. Drug availability is now supported by the World Health Organization. As part of another Global effort, the number of stillbirths reported through the network’s research fell by 30 percent as a result of the team teaching resuscitation techniques to birth attendants.

Ellen J. Plumb, M.D., of Thomas Jefferson University told the attendees that global health can be practiced at home as well as overseas, because 80,000 refugees and 27 million foreign-born persons now live in the U.S.

Many global-health physicians work within the U.S., including Dr. Khan and Karla Testa, M.D., both leaders in the Global Health Group at Christiana Care.

“Global health really is a large public health issue, even if you’re not traveling around the globe,” said Dr. Testa, who practices at Westside Family Healthcare, a federally qualified health center.

Statistics presented at the symposium underscored that: Each year, 1.4 billion people travel by air. Food and animals are sold globally. A virus can spread around the world in two or three days.

Dr. Plumb introduced several global health fellowships, but she emphasized that fellows could practice in the U.S. or overseas.

“Global health practice is here,” she said. “It’s in your back yard. You don’t have to go halfway across the world to do things.”