Your patient got a dense breast notification with her mammogram report: What are you supposed to do?

Diana Dickson-Witmer, M.D., FACS, and Arvind Sabesan, M.D.

This article first appeared in the Delaware Medical Society’s Delaware Medical Journal/March 2018 issue Vol. 90 No. 3 and is reprinted with permission.

Your patient got a dense breast notification with her mammogram report: What are you supposed to do?

The Annals of Internal Medicine, last spring, suggested the following questions that women should ask their PCP regarding breast cancer screening and prevention:1

- What is my personal risk for breast cancer?

- How often should I be screened?

- Should I be tested for the breast cancer gene?

This article will help you answer those questions.

Many of the women reading this article will have received the following notification with the report of their annual screening mammogram:

“Your mammogram shows that your breast tissue is dense. Dense breast tissue is common and is not abnormal. However, dense breast tissue can make it harder to evaluate the results of your mammogram and may also be associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. This information about the results of your mammogram is given to you to raise your awareness and to inform your conversations with your doctor. Together, you can decide which screening options are right for you. A report of your results was sent to your physician.”

Why are we getting these notifications? In 2003, Nancy Capello found a lump in her breast. She had stage III breast cancer. She was angry. She had a mammogram three months before and the cancer had not been seen. She began an impassioned national campaign to require radiologists to notify women when their mammogram is “dense.” She became a celebrity and legislation began to be passed in many states.2 Unfortunately, there are some significant problems with the emotion-driven rather than science-informed notification laws.

But first, what makes a mammogram “dense?” Breasts are composed of many elements: fat, milk lobules, milk ducts, blood vessels, and connective tissue. The lobules, ducts, blood vessels, and connective tissue collectively are called “fibroglandular tissue,” and they block the X-ray beam more than fat does. The ratio of fibroglandular tissue to fat in a breast determines the mammographic density, or how white or black the breast appears on the mammogram.

A mammogram that is “almost entirely fatty” looks darker. (Image 1) A mammogram of a breast with a little more fibroglandular tissue is a little whiter (Image 2). A mammogram of a breast with higher ratio of fibroglandular tissue to fat looks even whiter (Image 3), and a breast with almost no fat looks extremely white on a mammogram. This degree of density is called “extremely dense” and is present in about 8% to 10% of mammograms (Image 4).

Younger women, still in child-bearing years, typically have less fat relative to hormone stimulated fibroglandular tissue, and their mammograms are usually either “heterogeneously dense” or “extremely dense.” After menopause the glandular tissue normally begins to be replaced by fat, a process called involution, and the mammographic density decreases. There are some exceptions. Some young women, who are overweight and have a high BMI, may have less dense breasts. Some postmenopausal women with very low BMI, or who are taking female hormones, may have extremely dense breasts. And there are also some genetic influences that may affect breast density.

The distribution of levels of breast density for women of mammographic screening age reflects the factors age, BMI, and hormone status. About 10% of us have entirely fatty breast density. About 10% have extremely dense mammograms. The remaining 80% fall into one of the two intermediate categories: scattered fibroglandular elements or heterogeneously dense. Almost all radiologists agree about entirely fatty and extremely dense.3

There is no clear objective method of differentiating between the two intermediate categories.4,5,6

One problem with the dense breast notification laws is that they mandate sending the notifications not just to women with extremely dense breasts, but also to women with heterogeneously dense breasts. The two groups combined represent 50% of screened women. The current method of assigning breast density is quite subjective, with significant interobserver variation, especially between heterogeneously dense and scattered fibroglandular elements groups.

Legislators in over half of the United States were persuaded to require radiologists to notify women of their mammographic density because there are some actual problems related to increased breast density. In mammograms of extremely dense breasts, cancers are more difficult to see. This is called masking. White cancers hide in the white background. Masking is much less of a problem with tomosynthesis, or 3D mammography, than with earlier digital mammography technology. A 2D mammogram shows all layers of the breast superimposed on one another. Tomosynthesis shows one layer at a time, so things in front of and in back of a cancer do not hide the cancer.

The other reason that lawmakers were encouraged to pass notification laws is somewhat of a misconception. The advocacy groups state that “dense breast” is associated with high risk of breast cancer. This is not entirely true.

FACT: women with heterogeneously dense breasts, 40% of all of us, have a relative risk of breast cancer of 1.6 compared to women with entirely fatty breasts. That relative risk is less than the 1.7 RR associated with having one second degree relative with breast cancer, and less than the 1.8 RR associated with ever having had a breast biopsy.

FACT: the 8% to 10% of us with extremely dense breasts have a relative risk of 2.04 compared to women with completely fatty breasts. That is less than the 2.14 RR associated with having one first degree relative with breast cancer and much less than the 3.84 RR associated with having two first degree relatives with breast cancer.7,8,9

Dr. Kevin Hughes, Co-Director of the Avon Comprehensive Breast Evaluation Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, clarifies the issue of breast cancer risk and mammographic density by using the concept of “residual breast density.” By this he means the amount of breast density which exceeds what one would expect given an individual woman’s age, hormonal status, and BMI. A 40-year-old trim Asian Olympic athlete should have an extremely dense mammogram. An overweight postmenopausal woman, not taking HRT, should not have an extremely dense mammogram, and if she does, she has a risk factor for breast cancer, over and above her age and weight.10,11

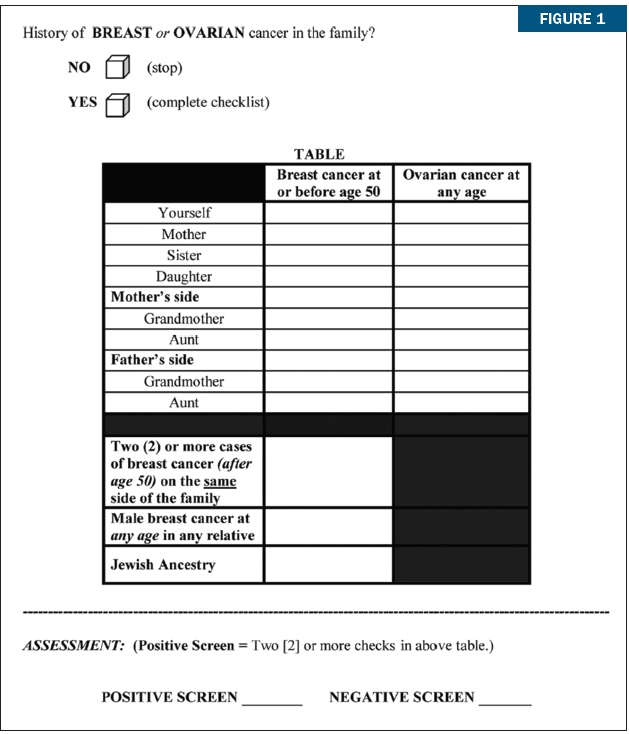

The Dense Breast notifications ask women to consult with their doctor to decide which screening options are best for them. If you are the PCP, you need a valid assessment of the woman’s breast cancer risk in order to advise her about screening. The first important step in assessing a woman’s risk of breast cancer is to take a careful three generation family history. This family history may reveal the possibility of deleterious germ line mutation. One quick tool to identify individuals who should be referred to a Genetic Counselor is the Referral Screening Tool. (Figure 1) 12

Genetic Counselors will use four computer models to further refine the estimate of breast cancer risk and of deleterious mutation. They will recommend testing if indicated, and for which mutations the patient should be tested. They are also enormously helpful at providing the data to third party carriers, which will result in coverage of any tests that are appropriate and in helping the PCP interpret the results of testing, which can often be nuanced.

Criteria other than family history also impact breast cancer risk. One free web based tool for breast cancer risk assessment, which is user friendly, validated, and takes into account many risk factors including results of previous biopsies, BMI and hormonal history, is the Tyrer-Cuzick Risk Calculator, available online at ibis.ikonopedia.com. This tool calculates the woman’s 10-year risk of breast cancer and her lifetime risk of breast cancer, and compares these to those of the general population.

Breast cancer risk assessment, if done well, is not possible in a 15-minute visit. To help doctors and their patients with this, the Breast Program at the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center has developed a “Breast Cancer Prevention Program.” The doctor or the patient can call 302-623-4343 and ask for a “breast cancer prevention visit.”

A specially trained PA-C member of our Breast Surgeons practice will meet with the patient, review her images, examine her, take a three generation family history, obtain any pertinent biopsy results, calculate a Tyrer-Cuzick lifetime risk, and make a personalized recommendation for that patient for screening and for risk reduction strategies. If the assessment indicates value for the patient in Medical Oncology consultation for chemoprevention or for Genetic Counseling referral, these referrals will be facilitated. A complete report of the findings and recommendations will be provided to the patient and to the PCP.

Armed with a metric for the woman’s risk of developing breast cancer, the PCP can offer suggestions in answer to the question: How often should I be screened? National societies are in an uproar over whether screening should begin at 45 or at 40. The guidelines are all over the board. The United States Preventive Services Task Force 2016 guidelines have a very high level of evidence, but they are not popular because they state honestly that vigorous examination of available data do not support annual mammography beginning at age 40.13 Guidelines from the American College of Physicians are fairly vague.11

The American College of Radiology recommends mammography every year from age 40, for all women. The American Cancer Society, in my opinion, strikes the best balance between being evidence based and being acceptable to the general public. The ACS recommends mammographic screening beginning at age 40 for individuals with risk factors for breast cancer, such as family history of breast cancer or personal history of breast cancer. The ACS recommends annual mammography for all women ages 45 to 74. At age 75 years, women who have no additional risk factors (other than age) may have biennial screening, and should continue as long as they have a reasonable expectation of ten years of life remaining. (Table 1) 14

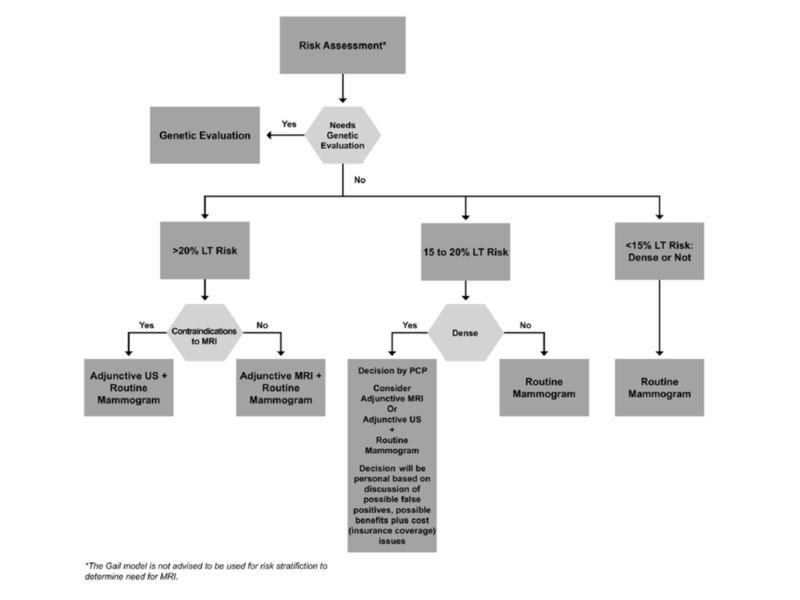

A frequently asked question, and one referenced in the mandated dense breast notification messages, is when to do MRI or ultrasound or other imaging modalities in addition to mammography for breast cancer screening. If tomosynthesis is the mammography technique used, most women do not benefit from adjunctive imaging modalities. After a PCP has determined whether genetic counseling referral is indicated and after determining lifetime risk (LT risk) of breast cancer using the Tyrer-Cuzick tool, a woman and her PCP could refer to the Massachusetts Breast Risk Education and Assessment Task Force algorithm (Figure 2) for deciding if additional imaging is needed over and above annual tomosynthesis mammography.18

If the lifetime risk of breast cancer (LT risk) is greater than 20%, the American Cancer Society recommends annual MRI in addition to mammography regardless of breast density. Women in this category include, but are not limited to, those with deleterious mutations such as BRCA 1 or BRCA 2, Li Fraumeni or Cowden’s, and women with a personal history of therapeutic mantle irradiation at or before age 30. If a woman’s LT risk (based on the Tyrer-Cuzick model) is less than 15%, she would not benefit from additional or “adjunctive” imaging, regardless of breast density.

Those women whose LT risk is 15% to 20% on the Tyrer-Cuzick model need to discuss with their PCP the problems versus the benefits associated with adding MRI or ultrasound to mammography for screening every year. The benefits might include finding a cancer at an annual screening versus finding it a little later when it becomes palpable. The risks include having many more call backs for additional imaging, having more biopsies for benign findings, and the fact that, at less than 20% LT risk, insurance may not cover MRI or ultrasound for screening since the benefit has not been shown to outweigh the risks.

It is in this 15% to 20% LT risk group that the mammographic breast density should be part of the conversation. In the 15% to 20% LT risk group, the masking effect of extremely dense breast tissue might be a reason to have adjunctive imaging in spite of the increase in false positives. Currently commercially available adjunctive imaging modalities are MRI and ultrasound. MRI increases the number of cancers found per 1,000 screens, but it also significantly increases the recalls and “false positive” biopsies. It also requires intravenous injection of Gadolinium, which may accumulate in the brain. MRI is also very expensive. Ultrasound screening increases cancer detection modestly, three to four per 1,000 screens, and increases recalls and biopsies by as much as 30%.

Tomosynthesis, compared to 2D digital mammography, increases cancer detection by one to four per 1,000 screens, and importantly, DECREASES recalls and iopsies by 15%. My recommendation to women in the 15% to 20% LT risk group is that they should have annual tomosynthesis and only have additional imaging if there are findings of concern on omosynthesis.19,28,29

In the next five years, we may see validated commercial availability of another form of breast imaging which, like MRI, is a molecular functional test, not just a morphologic test. Molecular Breast Imaging converts gamma-ray energy to electronic signals. The new “dual-head” configuration may detect subcentimeter tumors, an improvement over earlier versions. Single institution studies indicate that MBI may increase by eight per 1,000 screens the number of cancers found in women with extremely dense breasts. It does not involve Gadolinium, but it does require an injection intravenously. The radiation dose is slightly higher than mammography. There may soon be direct biopsy capability.20

There is one other question that women should ask their PCP. What can I do to reduce my risk of breast cancer?

For women at very high levels of risk, greater than 20% LT risk on the Tyrer-Cuzick model, or women with deleterious mutations, there is solid evidence that Tamoxifen and Evista reduce risk by 50%, 21 and that bilateral mastectomy reduces risk by 90%. 22 But this is a very small subset of women. These risk reduction modalities are not appropriate for the vast majority of women who will receive dense breast notifications. There are PREVENTION methods indicated for all of us, regardless of breast density or lifetime risk of breast cancer:

- Physical activity: 30 minutes of moderate physical activity 5x/week can reduce breast cancer risk 20% to 50%.23

- Smoking cessation: The risk of breast cancer is 24% higher among smokers than among non-smokers.24

- Weight control: Being overweight or obese after age 18 years increases the risk of breast cancer as much as 30%.25,26

- Reducing alcohol intake: Alcohol increases the risk of breast cancer, and the risk is proportional to intake. Keep alcohol intake down to no more than one alcoholic beverage a day on average.27

In summary

Breast density is not a strong independent risk factor for breast cancer, and most women with even extremely dense breasts do not benefit from screening MRI and/or ultrasound, as long as their annual mammogram is tomosynthesis.18,29

Whether a woman does or does not have dense breasts on mammography, each woman should gather a detailed three generation family history and meet with her PCP to discuss breast cancer risk assessment and, most importantly, RISK REDUCTION. Prevention is better than early detection.

References

- Nattinger AB, Mitchell JL; What you should know about breast cancer screening and prevention Ann Intern Med. 2016; 164(11): ITC81-ITC96

- Cappello NM. Decade of ‘normal’ mammography reports — the happygram. Journal of the American College of Radiology: JACR 2013; 10(12):903-8.

- Sprague BL, Gangnon RE, Burt V, et al. Prevalence of Mammographically Dense Breasts in the United States. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2014; 106(10).

- Redondo A, Comas M, Macia F, et al. Inter- and intraradiologist variability in the BI-RADS assessment and breast density categories for screening mammograms. The British journal of Radiology 2012; 85(1019):1465-70.

- Gard CC, Aiello Bowles EJ, Miglioretti DL, et al. Misclassification of Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) Mammographic Density and Implications for Breast Density Reporting Legislation. The Breast Journal 2015; 21(5):481-9.

- Checka, CM; AJR. 2012, 198, W292-W295

- Nelson, HD; Annals Intern Med. 2012; 156: p635-648

- Tice JA, O’Meara ES, Weaver DL; Benign breast disease, mammographic breast density, and the risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013; 105: p 1043-1049

- Gierach GL, Ichikawa L, Kerlikowske K, et al. Relationship between mammographic density and breast cancer death in the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2012; 104(16):1218-27.

- Hughes K; presentation at 33rd Annual Miami Breast Cancer Conference, March 10-13, Miami, Florida

- Natinger AB, Ann Intern Med, June 2016

- Bellcross CA; Genet Med; 2009:11(11): 783-789

- Siu AL, Annals of Internal Medicine; 16 February 2016; 164(4); P 279-296

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ETH, Herzig A; Breast Cancer Screening for Women at Average Risk 2015 Guideline Update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA; 2015;314(15):p1599-1614

- Perlman M, Jeudy M, Chelmow D; Breast Cancer Risk Assessment and Screening in Average –Risk Women. Practice Bulletin No. 179. Am College of Obstetricians and Gynecol 2017;130:el-16

- Monticciolo DL, Newell MS, Hendrick RE; Breast Cancer Screening for Average –Risk Women: Recommendations from the ACR Commission on Breast Imaging. JACR; Sept 2017;14(9); p1137-1143

- https://www.aafp.org/afp/2016/0415/p711.html. Accessed 1/20/2018

- Freer PE; Breast Cancer Res Treat; 2015;153(2):p455-64

- Throckmorton AD, Rhodes DJ, Huges KS, Degnim AC, Dickson-Witmer, D; Dense Breasts: what Do Our Patients Need to Be Told and Why?; Ann Surg Oncol; October 2016; DOI 10.1245/s10434-016-5400-3

- Rhodes DJ, Hruska CB, Conners AL, et al. Journal club: molecular breast imaging at reduced radiation dose for supplemental screening in mammographically dense breasts. AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology 2015; 204(2):241-51.

- Fisher B,Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: current status of the NSABP-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst; 2005; 97; p1652-62

- Hartmann LC, et a; Efficacy of Bilateral Prophylactic Mastectomy in Women with a Family History of Breast Cancer. NEJM 1999; 340(2); p77-84

- Dallal CM; Long-term recreational physical activity and risk of invasive and in situ breast cancer: the California teachers study. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Feb 26; 167(4); p408-15

- American Cancer Society’s Cancer Prevention Study II (CPS-II), Journal of the Natl Cancer Institute; Feb 28, 2013

- Reeves GK,. Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: cohort study. BMJ. 335(7630):1134, 2007.

- Eliassen AH, Adult weight change and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. JAMA; 296(2):193-201, 2006.

- Smith-Warner SA, Alcohol and breast cancer in women: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. JAMA; 1998;279:535-40

- Melnikov J, Ann Intern Med; Jan 2016,164; p268-278

- Aujero, M., MD, Holt, JS, MD Clinical Performance of Synthesized Two-dimensional Mammography Combined with Tomosynthesis in a Large Screening Population Radiology; April 2017,283(1) 70-76

Contributing authors

Diana Dickson-Witmer, M.D., FACS is a breast surgical oncologist and the medical director of the Breast Center and the Breast Program at Helen F. Graham Cancer Center and Research Institute.

Arvind Sabesan, M.D., is a chief General Surgery resident at Christiana Care who will be attending Moffitt Cancer Center to complete a surgical oncology fellowship.