Statistics present a sobering tally of the devastation caused by gun violence around the country and close to home.

- More than half of U.S. adults have experienced a gun-related incident, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

- Gun deaths are the leading cause of death for people between the ages of 1 and 20, according to The New England Journal of Medicine.

- Although serious crime has decreased in Delaware in the last decade, homicides more than doubled from 2017 to 2021, according to the Delaware Statistical Analysis Center.

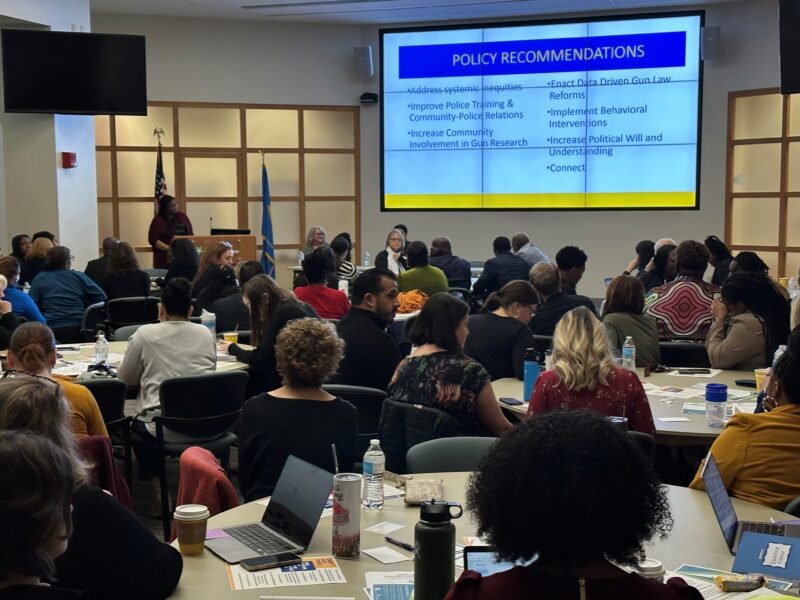

The pain and trauma inflicted by community violence can scar neighbors and neighborhoods just as deeply – only without the visible wounds. Those who attended the Community Violence Symposium recently hosted by ChristianaCare and the Coalition for a Safer Delaware already know the impact of gunshots and the threat of violence.

They see it in neighbors who won’t tell police what they saw during a shooting. Or teenagers who don’t see a future for themselves beyond the perimeter of their neighborhood. Or frustrated business owners who see no other option but to move out of the community.

“People will say they don’t live in fear, but actually, they are living with fear. If you say you can’t take your kids to the playground, you can’t walk your kids to school because of what’s happening in the streets, then all of that is playing on your mental health,” said David Chen, M.D., MPH, a hospitalist at ChristianaCare.

“When it comes to gun violence, you don’t have to be physically wounded to be impacted. People have these invisible wounds, these hidden wounds, but rarely is it asked about, especially if there are no physical health impairments.”

We need ‘every person in this room’

Chen was among the speakers who participated in the Community Violence Symposium, held Nov. 7 at Wilmington Hospital. The event drew more than 150 people, many from the surrounding Wilmington neighborhoods, to talk about research, solutions and ways to work together.

“There’s always a lot more happening with this issue than people are really aware of, so there needs to be an opportunity for those in the community to talk about the work they’re doing,” said Traci Manza Murphy, executive director of the Coalition for a Safer Delaware.

Panelists shared gun violence research, discussed local programs finding success working with people to overcome the effects of violence in the community and explored how resources and investments could be leveraged to develop potential solutions.

“People will say they don’t live in fear, but actually, they are living with fear. All of that is playing on mental health.”

David Chen, M.D.

“There is a very important conversation about mass shootings in schools and yet we are not talking about the gun violence that has been wreaking havoc in our cities for decades,” said Dorothy Dillard, Ph.D., director of the Center for Neighborhood Revitalization and Research at Delaware State University. “And that’s what we wanted to focus on and bring to the table.”

All efforts that are undertaken to address community violence must recognize the impact of structural racism, poverty and system inequities that have plagued many under-resourced communities for generations, said Bettina Tweardy Riveros, J.D., chief public affairs officer and chief equity officer at ChristianaCare.

“At ChristianaCare, we’re committed to ending disparities, to supporting health equity, to ensuring that people in our Wilmington communities don’t have a life expectancy that is 16 years shorter than people two miles west of the city,” said Riveros, noting that the lifespan for residents in some parts of Wilmington is significantly shorter than in nearby Greenville.

“We’re here to work on all the things that need to happen around addressing violence, and we know it can’t happen with all without every person in this room.”

Health care cannot be quiet about violence

Health care provides a unique opportunity to intervene on behalf of those who are impacted by community violence, said Chen, but the reality is that unless a patient sees a provider as a result of an acute injury, it’s often not something that often comes up in the conversation. And yet, it should.

“Health care has been quiet about gun violence,” said Chen, who said he provided emergency care to two people shot outside his home in northeast Wilmington when he was a medical resident.

“We don’t engage sometimes because we’re afraid of the politics of it or because we’re afraid of whether it will provoke a negative reaction. “But the reality is, it’s our responsibility as a health care system and as practitioners.”

‘An honorable exit out of a life of crime’

When people experience community violence, they often want to make a change in their life but they aren’t sure how to take the next step. That’s where Johanna Rodriguez, MSW, and the Empowering Victims of Lived Violence (EVOLV) program at ChristianaCare can help.

EVOLV is a hospital violence intervention program. Rodriguez, the program coordinator, and two community health workers visit patients who have been injured – shot, stabbed or assaulted – as a result of community violence.

They see patients at the bedside who have been admitted to the trauma units at Wilmington and Christiana hospitals after a violent altercation. They also reach out to those who have been discharged from the emergency departments. Their role is not only to follow up on their physical health, Rodriguez said, it’s to support the victims in any way they need, whether it’s helping them keep their utilities on, get compensation for their injuries or advocate with a provider.

“They’re connected to us because of the injury that they’ve sustained. Our community health workers are seen as partners, both for the hospital system and for the patients,” Rodriguez said.

“We’ve been able to partner with ChristianaCare’s health guides to get them connected to free legal representation. Our patients have been able to work out child custody agreements. We’ve even had patients request to go back to trade school and successfully finished trade programming.”

For free help with your health care from ChristianaCare Health Guides click here or call 302-320-6586.

Since 2019, the evidence-based Group Violence Intervention Program has operated with a collaborative approach in Delaware to help individuals at high risk for gang-related violence. The program helps participants stabilize their lives, address existing trauma and reduce their involvement in the criminal justice system by helping them to make mindful decisions about their actions and behaviors.

About 300 people participate in the program, the result of a partnership with law enforcement including the Delaware Attorney General’s Office, U.S. Department of Justice, Wilmington Police Department, Delaware State Police and other police municipalities throughout the state.

“Our purpose is to identify these individuals and provide them an opportunity to have an honorable exit out of a life of crime, and provide them opportunities for sustainability and stability,” said Javar Simpson, deputy director of the Group Violence Intervention Program in Delaware.

“We’re trying to increase their employment ability, access to health care, education, training and development – anything that is going to help them be better members of society and, ultimately, be able to sustain them as well as their families away from a life of crime.”

Expanding the conversation

Community leaders speaking at the symposium said this is a critical time to explore some of the underlying issues, such as poverty, racism and the inequitable distribution of economic resources and educational services, that contribute to division and distrust among many residents.

Even something as signing kids up for youth sports can be an exercise in futility for parents because of challenges associated with transportation, cost and child care, said Priscilla Mpasi, M.D., FAAP, a pediatrician and associate clinical director of Complex Primary Care and Community Medicine at ChristianaCare.

Some residents also may be hesitant to venture out of their neighborhood into another part of the city, creating geographic divides that can impact how they access needed services, said Dorrell Green, superintendent of Red Clay School District.

“We wonder why things might spill over at a football game, when really, there is no connection to community. A resident may not go to the north side because they live on the west side,” Green said. “We need to look at how we’re defining community and really break down some of these structural silos.”

Event sponsors included Wilmington City Council, Delaware Department of Health and Social Services, Delaware Children’s Department, Everytown for Gun Safety and Nemours Children’s Health. The symposium was supported by the Delaware Racial Justice Collaborative, a partnership program of the United Way of Delaware.

Photos courtesy of Coalition for a Safer Delaware.