Like no other time in history, scientists are now able to treat inherited diseases. But because the scientific and medical communities have not sufficiently engaged diverse communities of color, there is a danger of developing genetic medicine based on databases of information only from European Caucasians.

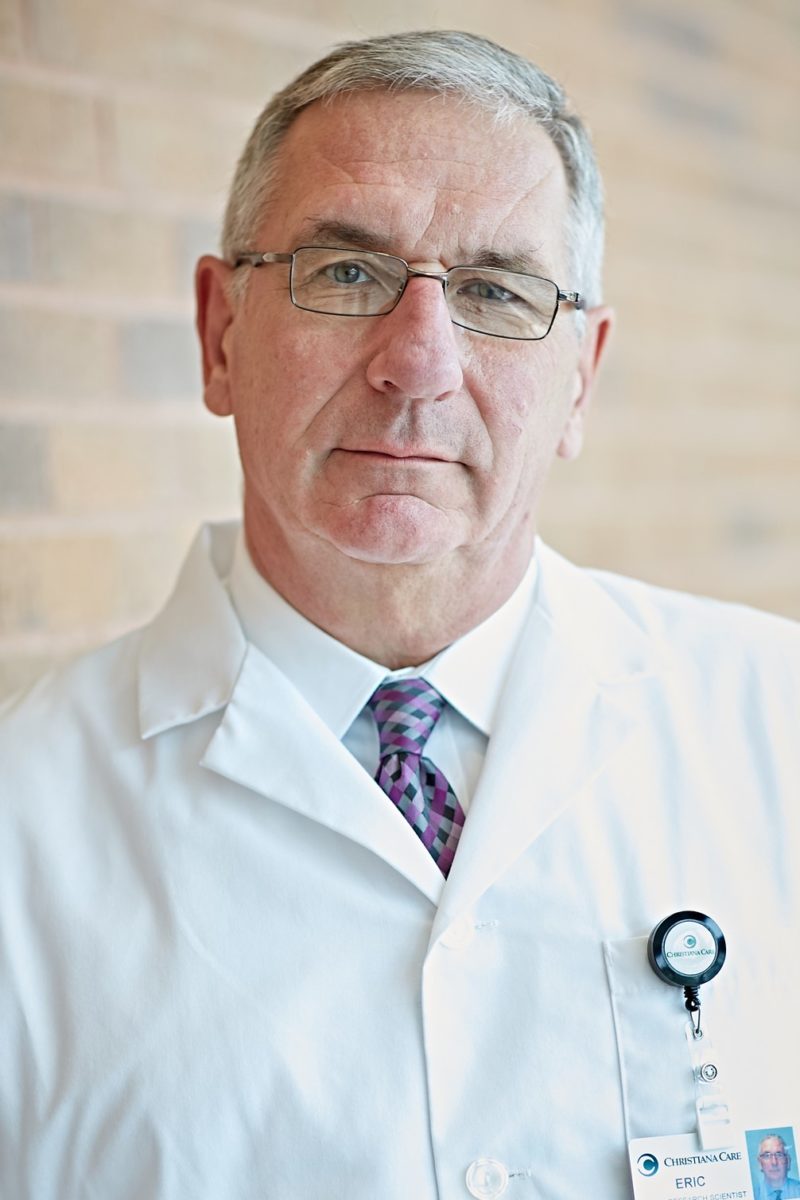

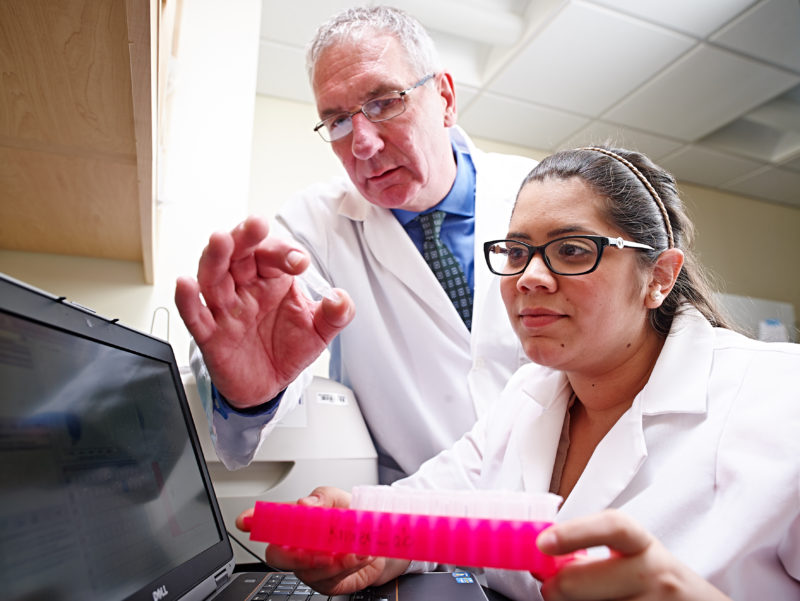

Sounding this alarm was Eric Kmiec, Ph.D., director of ChristianaCare’s “Gene Editing Institute at Building Trust: Reducing Disparities in Clinical Trials,” a panel discussion broadcast live on DETV, The televised conversation stems from a partnership between the Gene Editing Institute and The Franklin Institute to develop scientific and educational programing.

Joining Dr. Kmiec on the panel was host and moderator Jayatri Das, Ph.D., chief bioscientist at The Franklin Institute; Jacqueline Crawford, RN, patient/participant in a breast cancer clinical trial; Anya Harry, M.D., Ph.D., global head, Global Demographics and Diversity, at GlaxoSmithKline; and Holly Fernandez Lynch, JD, MBioethics, John Russell Dickson, M.D., Presidential Assistant Professor of Medical Ethics, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

So we can better treat inherited diseases, said Dr. Kmiec, “we desperately need people of color to participate in clinical trials and to donate samples so researchers can expand their databases that will enable them to develop drugs and genetic medicine so everyone can benefit.”

In a recorded interview with DETV Founder Ivan Thomas and broadcast on DETV prior to the event, Dr. Das said, “The world we live in now with Covid-19 has brought into focus a lot of the inequities in health care we have been living with for a long time.”

To better treat inherited diseases, “we desperately need people of color to participate in clinical trials so researchers can develop drugs and genetic medicine so everyone can benefit.” —Dr. Eric Kmiec

She cited the infamous Tuskegee experiments, in which scientists observed the effects of untreated syphilis in young black men and the infant mortality rate among Black babies in the U.S., which is three times higher than white babies.

A lesser known example, she said, is asthma. “Blacks and Latinos suffer from asthma more than other children. The most popular treatment is the drug Albuterol. It wasn’t until a few years ago that scientists involved more black and brown kids in studying how effective the drug was. They discovered that due to a genetic variation in the population, the drug doesn’t work as well for black kids and kids from Puerto Rican ancestry. Because the original studies were conducted on mostly white kids, scientists assumed that because it worked for them it would work for everyone.”

As a consequence of these and other events, many people in minority communities have lost trust in scientific research altogether.

Restoring trust in the scientific community

Panelists agreed that the scientific and medical communities need to better explain clinical trials and assure the public that they are now highly regulated and safe.

“There is an ethical obligation of the researchers to work with the communities they hope to study, to make sure they are asking the questions most important to those communities and that they understand the challenges and barriers that might arise in the course of research and medical care,” said Lynch, the ethicist from the University of Pennsylvania. “This includes working with communities to share the benefits and results of the research.”

When her physician offered Crawford the opportunity to participate in a clinical trial for her cancer, she was enthusiastic “because while it might not benefit me directly, my participation would benefit other people who have this type of cancer. I was told that not very many minorities participate in trials, so it was an opportunity to bring about change.”

She also learned that there were perks that made it advantageous for her to participate, including financial payment for her tests.

“It was a win-win,” she said.

“We work very hard to bring the voice of the patient into the trial,” said Dr. Harry, from GlaxoSmithKline. “We do that from the start as we develop the protocol. We get patient input about whether there are too many assessments, if the trial is too onerous or invasive. The voice of the patient helps us to get it right,” she said.

She also said pharmaceutical companies are “decentralizing” clinical trials by offering patients wearable devices in the home, using telemedicine for communication and sending nurses to the patient’s home to lessen the travel burden.

“Through technology we are trying to make it easier to participate in a clinical trial,” she said.