“I found this to be very worthwhile,” said Stephen Doyle, M.D., a first-year resident in emergency medicine. “The more experience you can have putting yourself in someone else shoes, the greater your empathy and the more you are able to appreciate the obstacles that patients face.”

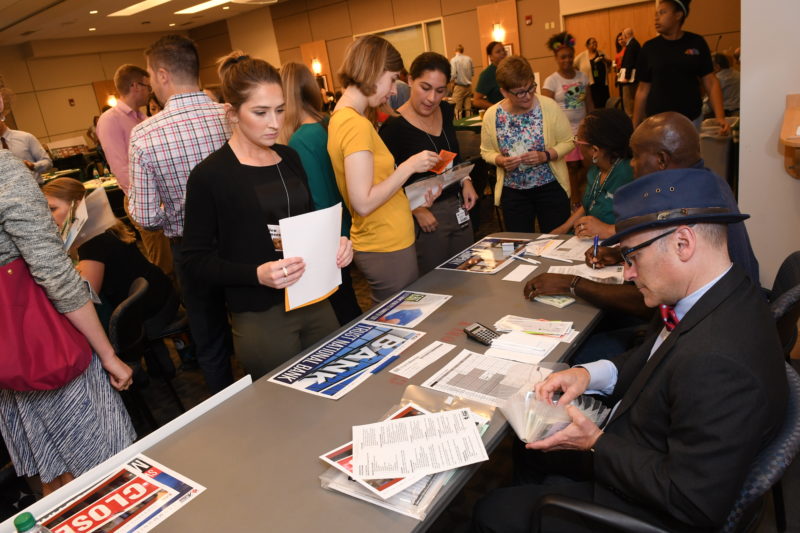

On June 21, about 90 residents took part in a Community Action Poverty Simulation, as an imaginary city was created inside the John H. Ammon Medical Education Center. There was a food market where only Spanish was spoken, a pay-day loan company, a transportation system, a school, a workplace, a health network, a police department and other services staffed by individuals from the greater Wilmington area playing the roles they actually perform in their real jobs in the community. One of the goals of the simulation is to give residents an awareness of community dynamics as well as resources available to patients.

The young doctors stepped into the responsibilities of a poor mother, father or child trying to make ends meet during 15-minute simulation segments representing a week in their lives. During a month of seeking to survive despite scarce resources, the stress on the residents intensified as they began to feel the tightening grip of compromises that individuals who live close to the poverty line make every day.

First-year psychiatry resident Sana Sharma, M.D., portrayed a 9-year-old taking care of a 7-year-old brother with a learning disorder. With her mother incarcerated and the whereabouts of her father unknown, Dr. Sharma, her brother and grandparents were surviving on her grandfather’s $500 disability check. And it wasn’t enough.

“I wanted to help out my family, and I was surprised, because I am normally a very law-abiding person, but my first instinct was to do whatever I had to do,” she said. “So I robbed my neighbors. I took anything I could get my hands on.”

For Dr. Sharma, the simulation was a valuable experience, in that she found health care to be a lesser priority as day-to-day survival became her focus. “These are things you don’t normally think about, and I hope to remember this,” she said. The simulation gave her a new understanding of why patients might have a difficult time making appointments and why they are not able to pay for medications.

Christiana Care provides a clinical learning environment for more than 280 residents within various programs. For the last three years, the poverty simulation has been an important immersion experience during orientation week to sensitize new residents to the issue of health equity and the everyday realities of Delawareans who struggle with low income and in impoverished neighborhoods, said Dana Beckton, director, Diversity and Inclusion. “This is a good way for the residents to have an early sense of where some of their poorest patients are coming from and the concerns they bring into the health care setting,” she said. “It is an awakening for many of these young people.”

Each year the poverty simulation has been co-led by Beckton and Jacqueline Ortiz, MPhil, director, Health Equity and Cultural Competence. They say that physicians in training are well-positioned to establish a new culture of medicine with an appreciation for diversity, disparities in care and social determinants of health. But for teaching hospitals, there has been no standardized method for training residents on these issues, and there have only been limited opportunities for busy residents to interact with local communities.

“The more experience you can have putting yourself in someone else shoes, the greater your empathy and the more you are able to appreciate the obstacles that patients face.”

As a result, the Alliance of Independent Academic Medical Centers has fostered an initiative to advance health advocacy through resident education that seeks to help clinicians better understand vulnerable and marginalized populations, said Robert Dressler, M.D., MBA, quality and safety officer, Christiana Care iLEAD. For Christiana Care, which has developed a curriculum around this theme, the poverty simulation is the first training for residents on the socio-economic determinants of health.

OB-GYN physician Arlene Smalls, M.D., a leader of the curriculum initiative to advance health advocacy through education, says the poverty simulation was selected because it has been used effectively in different settings around the nation, though Christiana Care is one of the first teaching hospitals to use it with first-year residents.

In June, representatives from Drexel University observed the simulation, and they have scheduled two such events in late August for medical students and second-year residents, with Christiana Care representatives participating in both, said Dr. Smalls.

After the poverty simulation, residents surveyed are less likely to agree that “people on low incomes do not have to work as hard because of all the services available to them” and “people are generally responsible for whether they are poor — they get what they have earned or deserved.” However the research on the simulation is still in its early stages, said Loretta Consiglio-Ward, MSN, RN, education specialist, Quality and Safety, Institute for Learning, Leadership and Development (iLEAD).

Since the first simulation in 2016, when representatives of six hospital-based resources as well as six volunteer community organizations were recruited to participate, community participation has been an important element.

“Many residents go straight through high school, college and medical school, and so they know medicine, but when they go to take care of people they don’t always know how to connect people to the broader services they need,” said Lisa Maxwell, M.D., associate chief learning officer. “We aim to help our learners become mindful and compassionate clinicians who are engaged in their local community.”

To help make that connection, Suzanne Tait, program director of the Beautiful Gate Outreach Center, has volunteered to be part of the simulation each year. As an HIV-AIDS counseling service, Beautiful Gate helps Wilmington residents understand their health status and assists clients with a broad array of social services when they need referrals.

“I’m here because I want the residents to know that we are a community resource available to help their patients,” said Tait. She also devoted a morning to the simulation because she believes in its goals.“I am a big supporter of this program,” she said. “If you haven’t lived in poverty, it’s hard to imagine it, and the simulation allows that to happen. I also think humanizing what low-income people experience allows the residents to empathize with their patients — and that makes them better doctors.”