Diana Dickson-Witmer, M.D., FACS, surgeon and medical director of the Christiana Care Breast Center and Breast Program at the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center & Research Institute, is the senior author of an article published in the Annals of Surgical Oncology, October 2016, outlining an evidenced-based approach to counseling and screening patients with dense breasts.

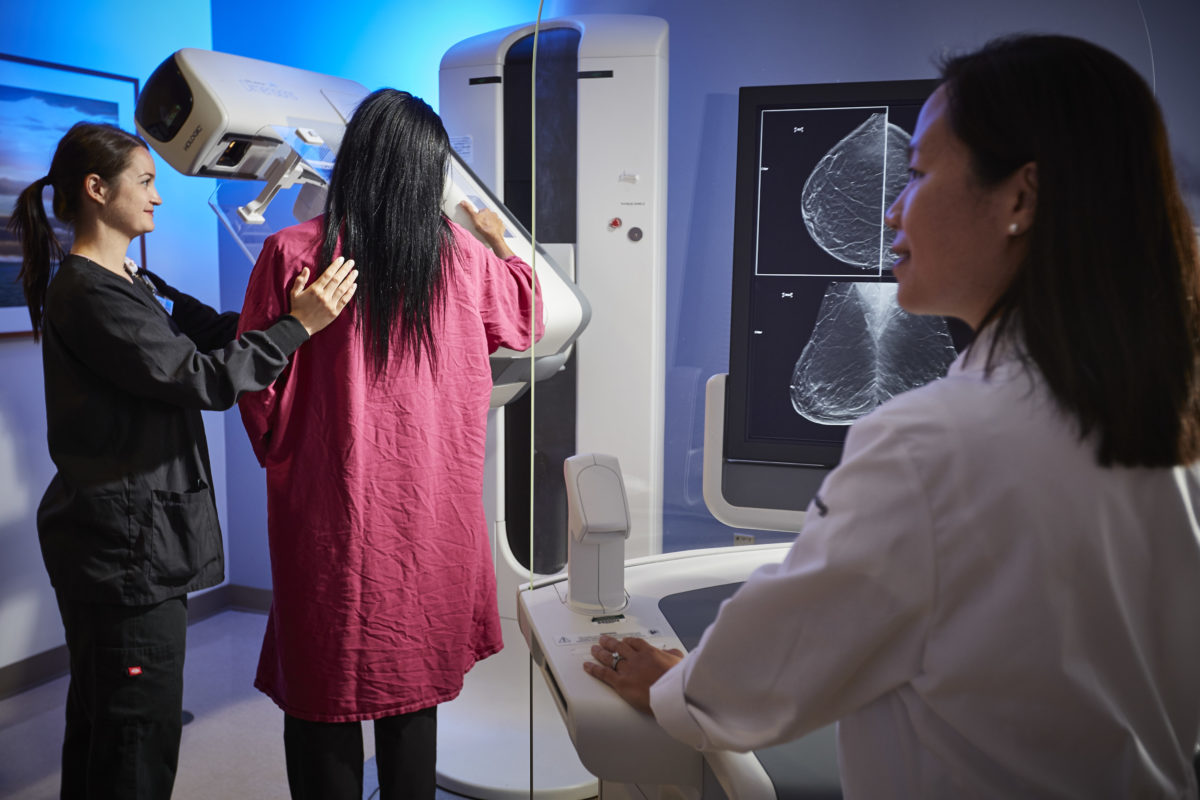

Currently 27 states, including Delaware, have mandated that mammography reports include information about a woman’s breast density and a recommendation that she talk with her doctor about the benefits of additional screening with MRI, 3-D mammography or ultrasound.

Although both MRI and ultrasound can detect breast cancers not easily seen on a mammogram, the downsides are more false positive readings, more recalls, more benign biopsies and higher costs that may not be covered by insurance. There is also the potential for over-diagnosis and treatment since some cancers found with these adjunct imaging modalities may never become clinically significant.

“When women talk about their mammographic breast density with their doctor, all of the other risk factors for developing breast cancer and risk reduction strategies should be part of that conversation,” Dr. Dickson-Witmer said.

Nearly half of all women undergoing screening mammography in the United States have what doctors describe as dense breasts — less fat, more fibrous glandular tissue. Increased breast density makes it harder for the radiologist to spot cancer on a mammogram, potentially making screening mammography less accurate for women with dense breasts.

“We think it is really important that breast density not be looked at as a stand alone critical element in a women’s risk of developing breast cancer, because it isn’t,” she added. A woman’s family and personal medical history, smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity after menopause and lack of exercise also factor in. “Only about 8 to 10 percent of women have extremely dense breasts. They may have a two-fold risk over the general population for developing breast cancer, but that is still a relatively low risk.”

The authors originally presented their recommendations as a panel moderated by Dr. Dickson-Witmer, at the American Society of Breast Surgeons Annual Meeting, held in Dallas, Texas, last April. They point out that currently there are no definitive, evidenced-based guidelines for screening based on breast density alone.

Their effort to clear a pathway to care for women with dense breasts may be the first on this subject to appear in a major surgical journal.

“Take the opportunity to talk to women about their other risk factors, whether they should see a genetics counselor, and what behaviors they can change to reduce their risk for breast cancer,” she said. Risk-reducing medications such as tamoxifen or raloxifene are also options for some women.

To aid in that discussion, the authors recommend surgeons use one of several evidenced-based breast cancer risk assessment tools, such as the IBIS Breast Cancer Risk Evaluation Tool developed by the International Breast Cancer Intervention Study, also known as the Tyrer-Cuzick model.

The model uses personal and family history, including genetic history, and lifestyle factors to calculate a breast cancer lifetime risk percentage value. Doctors can then plug that value into an evidence based algorithm (the Massachusetts Breast Risk Education and Assessment Task Force algorithm, for example) to determine whether additional supplemental screening is indicated. The algorithm recommends MRI screening for women with greater than 20 percent lifetime risk on the Tyrer-Cuzick (IBIS) risk model, no adjunctive screening for women with less than 15 percent risk and consideration of adjunctive screening with MRI or ultrasound for women with lifetime risk of 15-20 percent.

Experts agree and medical evidence supports the advice that any woman, regardless of her breast density, who falls in the high-risk group (greater than 20 percent lifetime risk, based on genetics, family history of breast cancer and other factors) should have an MRI along with her yearly mammogram. On the other hand, if her lifetime risk is less than 15 percent, she is less likely to benefit from supplemental imaging, regardless of breast density.

“The intermediate group (lifetime risk of 15 to 20 percent) is the only group where breast density should be taken into account for adjunctive screening,” said Dr. Dickson-Witmer. “We recommend tomosynthesis (3-D mammography) as the first line screening modality of choice for these women, if available.”

Women in the intermediate category should consider additional screening with MRI or ultrasound, if tomosynthesis is not available, but a conversation with their doctor about the benefits and drawbacks of these methods is essential.

Studies show that initial screening with 3-D mammography, particularly for women with dense breasts, can find additional cancers, with fewer callbacks for additional images and fewer false positives than a 2-D mammogram.

The Christiana Care Breast Center offers 3-D mammography at both the Graham Cancer Center and Concord Health Center locations.