A decade-long partnership between clinician scientists at ChristianaCare’s Helen F. Graham Cancer Center & Research Institute and The Wistar Institute has produced a new and unique opportunity to examine risk factors linked to triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) in Delaware neighborhoods.

The multilevel study is the first of its kind in Delaware and among only a few in the nation to examine a person’s biological cancer risk factors in the context of the neighborhood in which she lives. Another unique aspect is the multidisciplinary team itself.

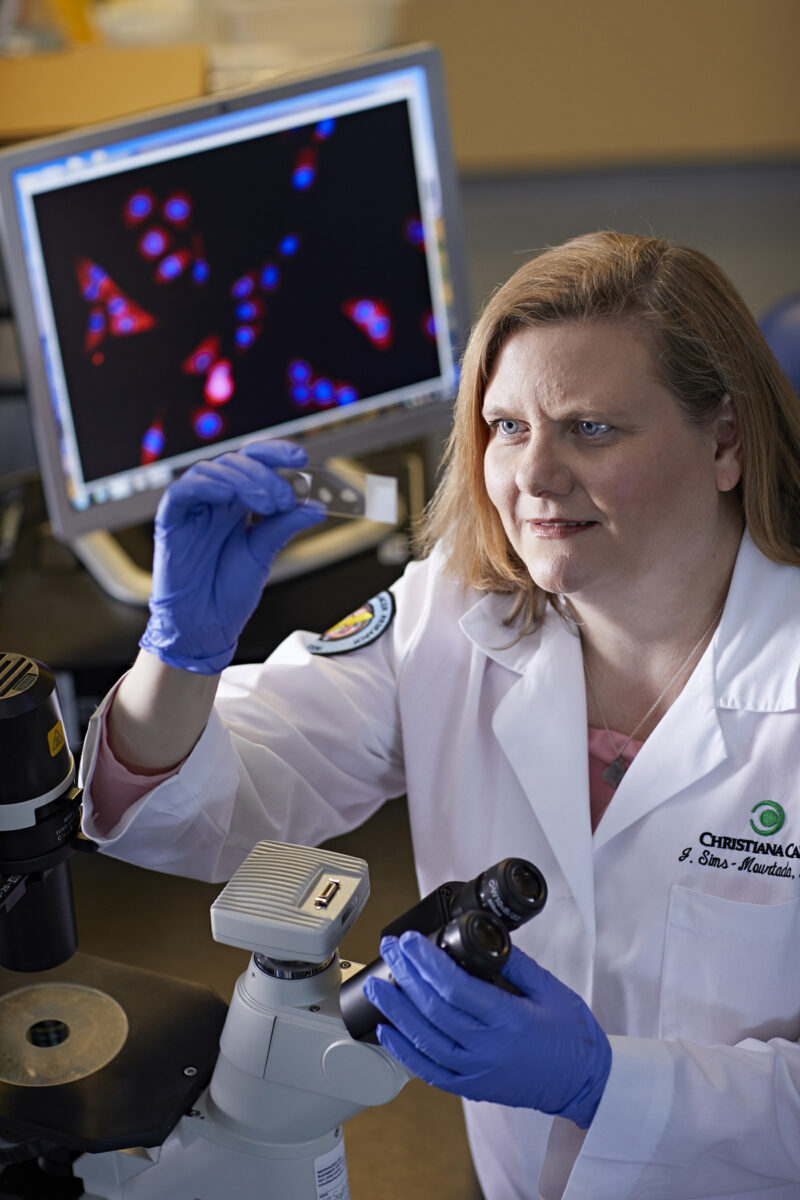

ChristianaCare lead scientists are Director of Population Health Research Scott Siegel, Ph.D., MHCDS, who is also a member of the ChristianaCare Institute for Research on Equity and Community Health, and Lead Research Scientist Jennifer Sims Mourtada, Ph.D., at the Graham Center’s Cawley Center for Translational Cancer Research. They are joined by Zachary Schug, Ph.D., assistant professor at the Wistar Institute Cancer Center’s Molecular and Cellular Oncogenesis Program.

“There are many risk factors for breast cancer that can be modified such as diet, exercise and alcohol consumption,” Sims-Mourtada said.

“If we can find a biomarker to identify someone at higher risk, we can modify those risk factors and potentially prevent or alter the course of this disease.”

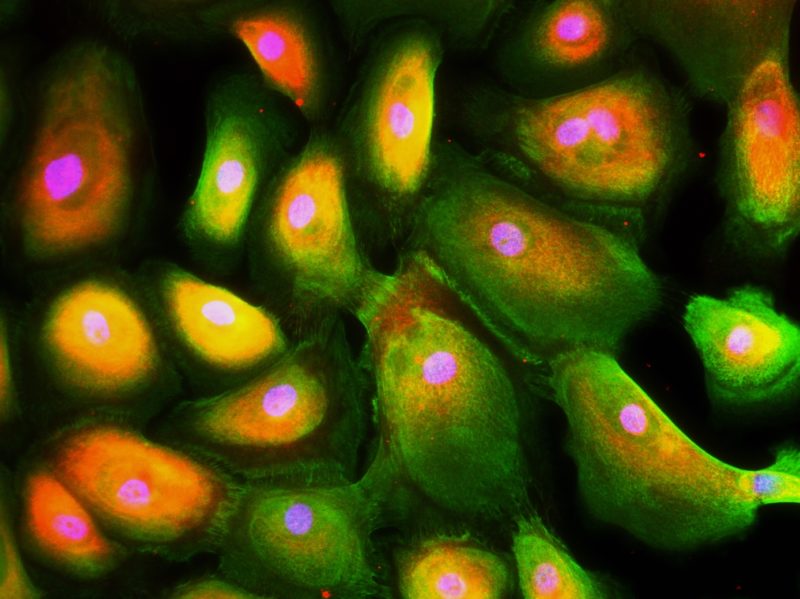

Sims-Mourtada’s research interests include the effects of inflammation and alcohol metabolism on breast cancer. Although it is not widely known, alcohol is an established risk factor for breast cancer.

Sims-Mourtada is particularly interested in the actions of an alcohol enzyme called ALDH (alcohol dehydrogenase) that plays an important role in breaking down alcohol molecules and eliminating them from the body.

“ALDH is over expressed in breast tumors and has been associated with poor outcomes,” said Sims-Mourtada.

“I am very interested in the function of this enzyme and its role in tumor growth.”

“We are looking at the whole person, not only what is happening inside her body but also how that correlates with what is happening outside in her environment.”

— Jennifer Sims-Mourtada, Ph.D.

Up to now, her research has focused on tumor biology and genetics, but Sims-Mourtada says the new study takes a broader systemic approach.

“This time we are looking at the whole person, not only what is happening inside her body but also how that correlates with what is happening outside in her environment,” she said.

“We are asking questions like what she is eating and drinking, and how that is affected by where she lives and what is happening in her community.”

Delaware ideal for study

Delaware ranks highest in the nation for the incidence of TNBC, an aggressive form that affects African American women at twice the rate of white women with poorer outcomes. Delaware also has the highest rate of alcohol-attributable breast cancers.

In this study, the researchers are looking at potential contributing factors such as diet and alcohol use along with genetic variants and the effects of these on cancer metabolism among women in Delaware and surrounding areas.

“Our large and diverse patient population makes the Graham Cancer Center ideal for this kind of study,” Siegel said.

The Graham Cancer Center provides care to some 600 patients annually which account for about 85% of the total cases from New Castle County, Delaware.

Looking at patient records over an eight-year period from the Graham Cancer Center registry, the team identified clusters of high TNBC incidence in two distinct areas of New Castle County.

“Once we found hot spots, we began to look at both clinical and demographic factors among the women in these areas including obesity and unhealthy alcohol use as well as neighborhood characteristics such as the number of alcohol retailers or the limited options to purchase healthy foods,” Siegel said.

“We know that black women are at increased risk for developing TNBC, but the risk is also increased for both white and black women who live in certain neighborhoods,” he said. “Our findings so far provide even stronger evidence that neighborhood and environment may be contributing to that risk.”

The team published results of their initial population health assessment in Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention in January 2022.

‘This is where science needs to go’

They plan to pursue grant funding to support what promises to be a multimillion-dollar study to continue over the next several years.

The next phase of the study will add a human tissue component to support the research of both Sims-Mourtada and Schug with samples provided through the Graham Cancer Center’s Tissue Procurement Program.

“I think the multilevel approach we are taking with this type of socio-biological analysis is extremely unique,” Schug said.

“We each have our expertise and by combining our knowledge we can achieve something not one of us could have achieved on our own. This is where science needs to go.”

Schug’s expertise at Wistar is in cancer metabolism. He uses a technology called mass spectrometry to analyze blood plasma for metabolites and lipids that could potentially be biomarkers for advanced breast cancer.

“Partnerships like ours with the Graham Cancer Center are extremely important if we want to have access to patient samples not only for my work but for the entire Institute,” Schug said.

Using machine-learning software the team continues to analyze their collective data to draw relationships between identified cancer hot spots and modifiable risk factors.

“We might identify a patient with a high amount of a certain metabolite in their blood, for example, that strongly correlates with their alcohol drinking pattern, which in turn could be driven by how closely they live to an alcohol retailer,” Schug said.

Hot spots with high rates of triple-negative breast cancer may correlate to rates of alcohol use and obesity and neighborhood characteristics such as multiple alcohol retailers and limited options to buy healthy foods.

“In addition, we can examine whether that person has a genetic mutation in their DNA that could contribute to how their body metabolizes alcohol.

“From that we can try to determine if by-products of that metabolism are potentially tumor causing, and whether they are contributing to her advanced breast cancer.”

Community outreach and collaboration have long been a priority for the Graham Cancer Center and that includes targeted programs in underserved neighborhoods to spread the word about the risk factors and prevention for TNBC. Those efforts will be supported and informed by ongoing study findings.

“What we are very interested in is looking at how these data we are collecting can help women now,” Siegel said.

“As we continue our study, we are looking closer at the communities where we see the highest level of risk, and expanding relationships with various stakeholders to improve cancer prevention and control,” he said.

“In a lot of ways our community is representative of the country’s demographics, which could make our findings of interest to other places well beyond our own local area.”