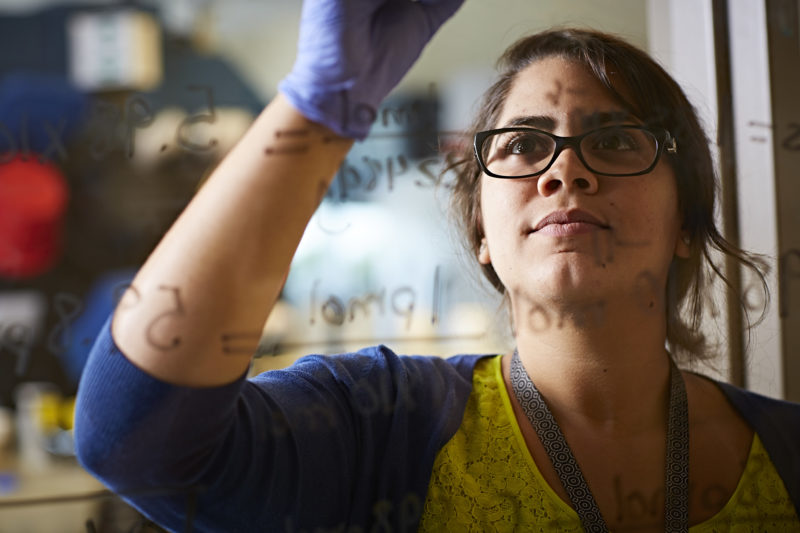

Working at the ChristianaCare Gene Editing Institute, research scientists Natalia Rivera-Torres, Ph.D., and Brett Sansbury, Ph.D., see something that most career scientists don’t — other women in the lab. Women make up nearly two-thirds of the staff in the Gene Editing Institute, an anomaly in a field where less than 30 percent of the world’s researchers are female, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

Rivera-Torres and Sansbury, who both have earned international recognition for their work with gene editing, want to make sure other female researchers also experience encouragement and a collaborative, welcoming environment.

They’re doing more than just talking about it — Sansbury’s research led to the creation and production of CRISPR in a Box, an educational kit designed for use in high schools and community colleges to help train the next generation of genetic scientists and technicians. Rivera-Torres also visits schools and life science organizations and challenges them to create more opportunities for promising students from backgrounds who have been traditionally been underrepresented in science.

In the spring, the two women also penned an op-ed for CNN.com about the need for the scientific community to start breaking down the barriers facing women in science. Rivera-Torres and Sansbury say this work needs to start early and intentionally by exposing elementary, middle and high school students to examples of scientists who look like them to show what’s possible. It continues in higher education through the addition of more women in faculty and research positions. And it spreads outside the classroom, they say, with engagement activities that also help the public reimagine what it means to be a scientist.

Both women credit the atmosphere created by Gene Editing Institute Director Eric Kmiec, Ph.D., with helping them grow professionally and personally. Working in a lab designed to support women encourages diverse thinking and collaboration that has allowed them to thrive and seek out leadership positions that they might not otherwise consider.

“I would not have thought I would be the leader of a discovery research group. Now I see that I can be. But that’s not something you just fall into. That’s something that you’re shown and taught how to do, not only through professional development but also within the research itself. Not having someone tell you the answer, but showing you how to find the answer,” Sansbury said.

“We want to foster really strong researchers and people in general. I think the biggest thing about it that is you can actually see yourself doing things.”

Although women have traditionally been underrepresented in science, Rivera-Torres and Sansbury say the success of contemporary female scientists has motivated and excited them, particularly Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020 for the development of the genetic editing device known as CRISPR. They say that’s why opportunities like the CRISPR in a Box program are important for inviting young minds to pursue the world of science.

For Rivera-Torres, making the leap to a scientific career meant leaving her home in Puerto Rico and moving to Delaware for graduate school. It was a hard adjustment, she said, but Kmiec’s support helped her navigate those changes and spurred her on to continue her passion in gene editing. Although she is still early in her career, Rivera-Torres has already been credited with helping researchers understand how gene repair is carried out and how it can vary in patient samples.

“I think the one thing that always was in the back of my mind was, ‘How am I going to fit in? Are they going to be bothered that I may have language barriers? Am I too loud with my Puerto Rican culture and will that get in the way of them taking me seriously?” said Rivera-Torres, who serves as operations manager for the Institute and has been with Kmiec’s lab for eight years.

“Sometimes, being different and being bold is frowned upon,” she said, “but not here. We need more of that. We need to encourage those young minds to start thinking about different problems using that creativeness and critical thinking and innovation because this is an innovative field. You don’t want them to lose that spark.”

Kmiec said it’s critical to promote the success of young researchers like Rivera-Torres and Sansbury to expand the pipeline and change the narrative about who can be a scientist.

“I think they make a bigger impact because it isn’t just about the competitiveness of what we do here or the intensity — it’s about delivering that message to the next generation,” he said.

The Gene Editing Institute and DETV partnered on an educational video series to inspire high school students to enter one of the most exciting careers in science and medicine today – CRISPR gene editing.

As they get further in their careers, Rivera-Torres and Sansbury say they are excited by the opportunities available not just to them, but future scientists who may not even realize the kind of options available to them.

“They might think to themselves, ‘Am I ready to join such a big institution?’ Here we are in our first big job within a big institution, a very big lab, and we’re making it,” Rivera-Torres said. “We leave the mark for them to follow us.”

Sansbury agrees. “We had a space made for us. And we should make a space, too.”