Among patients who have been successfully treated for throat cancer, a common side effect of treatment is damage to the salivary glands. The radiation used to kill the tumor can also cause the salivary glands to stop working, which can make normal activities like eating, swallowing and talking difficult and painful.

At Christiana Care’s Helen F. Graham Cancer Center & Research Institute, cancer researchers Robert Witt, M.D., FACS, and Swati Pradhan-Bhatt, Ph.D., are on a quest to solve this problem through the development of artificial salivary glands.

“Our goal is to return the function of the patient’s salivary glands and reduce human suffering … to relieve the debilitating lack of saliva in a patient who has undergone radiation treatments,” said Dr. Witt, the clinician/scientist principal investigator in the four-year initiative that began in 2012, and director of the Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Oncology Clinic at the Graham Cancer Center. “These are patients who have lost the ability to swallow properly, to enjoy food and liquids, and lack a sense of taste. They also are prone to many dental problems.”

Working at the Center for Translational Cancer Research at the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center & Research Institute, Dr. Witt and Dr. Pradhan-Bhatt are national leaders working toward the development of artificial salivary glands. The research focuses on ways to grow cells taken from patients before they undergo radiation treatment. Ultimately, doctors will re-implant the patients’ own cells back into their damaged salivary glands when radiation is complete, enabling them to restore their salivary glands.

Even before the launch of the National Institutes of Health funded study, Dr. Witt began the research with financial help from the philanthropy of a patient. His early success helped advance the research to a level where a proposal in 2012 for federal funding from NIH’s National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research became feasible.

Dr. Pradhan-Bhatt is senior research scientist and director of tissue engineering at the Center for Translational Cancer Research. Early in her work with Dr. Witt and Cindy Farach-Carson, Ph.D., vice-provost for Translational Bioscience at Rice University in Houston, she discovered a technique to isolate salivary acinar cells in a lab culture. Acinar cells are one of three basic building block cells — responsible for water and enzyme production — comprising salivary glands.

Now in the fourth year of the four-year grant, researchers under Dr. Witt and Dr. Pradhan-Bhatt have isolated and observed how another building block cell, the myoepithelial cell, found wrapped around the secretory lobule in native tissue, undergoes contraction in response to a neurotransmitter chemical that activates a biological response. This contraction is thought to be the major way in which saliva is expelled from the secretory lobule so that it can flow into the mouth.

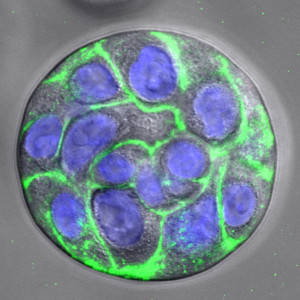

“We are trying to follow the actual steps of human development, where the salivary gland cells start to branch, just like you would see in a growing tree,” said Dr. Pradhan-Bhatt. “These branching structures require the same growth factors and extracellular matrix proteins found in human development, yet it can all occur in the lab within a cell-friendly scaffold or housing called a hydrogel, which is human-compatible and absorbable.

“Additionally, Dr. Xinqiao Jia, a materials scientist/engineer at the University of Delaware, has invented micro- and nano-sized hydrogel particles that can be added into our hydrogels to allow for growth factor release into our implants. The scaffold allows cells to grow in spheroid structures that merge, forming lobes that closely resemble the ones found in the developing salivary gland. Working with our materials science and engineering colleagues, we are trying to tune the properties of the hydrogels as closely as possible to mimic the native human tissue microenvironment.”

Other principal investigators named in the 2012 NIH grant include Dr. Farach-Carson and Dr. Xinqiao Jia. The team also includes Randall Duncan, Ph.D., professor, Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Delaware, and Dan Harrington, Ph.D., from the BioSciences Department at Rice University. “Their work is of enormous importance, and they play an essential role in this great honor,” Dr. Witt said.

Research project grants, known as R01, are highly competitive. NIH awards them to specified projects that a named investigator or investigators perform. Dr. Witt is the first physician at Christiana Care to achieve the role of Principal Investigator for an NIH grant through work done at Christiana Care. The team is preparing to make application for a four-year extension of funding for the project.

The Center for Translational Cancer Research seeks to quickly move laboratory “bench” research to the bedside by applying basic science toward potential therapies. Established in 2004, the Center for Translational Cancer Research is a formal collaborative program among the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center & Research Institute, the University of Delaware, A.I. duPont Children’s Hospital and the Delaware Biotechnology Institute. It also includes the High-Risk Familial Cancer Registry and the Tissue Procurement Center.